Matera: a ride from Rome in the city of sassi

You know there must be something particularly special about a place when, despite the distance from transport hubs and tricky arrival logistics, it suddenly starts popping up on dream itineraries and bucket lists from glossy travel magazines to backpacking blogs. The ancient city of Matera is one of those difficult yet rewarding special places, located in the extreme southern province of Basilicata just a few kilometers from the border with Puglia, and tumbling down a canyon ridge overlooking the neighboring Murgia Materana Park. Not particularly near any principal airports, and set a bit off by itself at the point where the Salento peninsula “heel” attaches to Italy’s “boot”, this hauntingly beautiful place is unique and memorable enough to have been named both a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993 and, just this year, the European Capital of Culture for 2019.

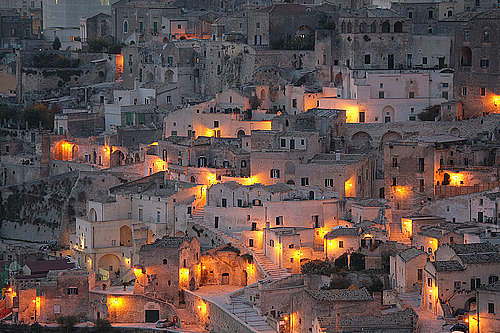

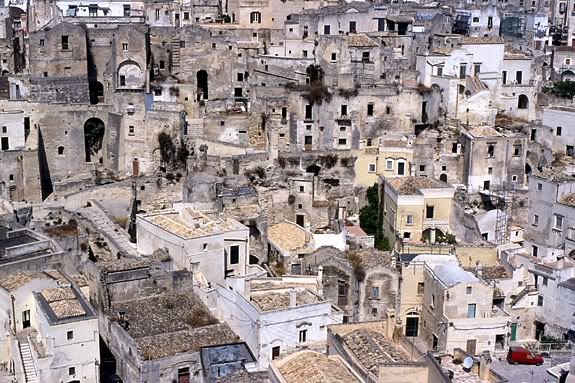

The History of Matera At first glance, it would be easy to mistake Matera for a Middle Eastern city (indeed, parts of Mel Gibson’s “The Last Temptation of Christ” were filmed here), with its jumble of squared-off, whitewashed buildings crowded haphazardly one on top of the other in the old town, known as the Sassi di Matera, or the stones of Matera. Thought to be the site of the first human settlements on the Italian peninsula, this steep slope was formed over millennia by the erosion of the river Gravina, and the square houses tumbling down the canyon wall are actually entrances into a hidden underground honeycomb of caverns, dug out of the relatively soft sandy rock by generations of settlers who expanded the ridge’s natural grottoes and used them over time as houses, churches, and shops.

Sadly, Matera has been known for much of the past two centuries as one of Europe’s most impoverished cities. The thousands of local caves, Italy’s oldest continually inhabited settlements, housed families living in such shocking squalor that the Italian government was forced to rehouse the 20,000 people who were still surviving there without electricity, sanitation, and basic civic services in the 1950s.

For decades, the ancient town was abandoned and largely forgotten (or, better, a shameful symbol rarely spoken of publicly), aside from a small group of squatters who began moving in during the 1970s. From there, a quiet Renaissance began, as the barren center was slowly re-inhabited and renovated, and hip cafés, high-end hotels, art galleries, and chic retreats for artists and writers began taking over the more inhabitable caves.

Today, Matera is a fascinating and vibrant town, with a labyrinthian center of twisting alleys and dead ends, steep staircases and buildings built one on top of the other. In just a few steps, visitors move from eerily barren and silent quarters, where the stark poverty of the past is easy to imagine, to buzzing newly renovated neighborhoods crowded with unique cave restaurants and hotels, where the misery of just a few decades ago seems to belong to a different age altogether.

What To Do in Matera? Stay in a cave hotel.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this town are the ancient cave dwellings, some of which have been transformed into one-of-a-kind hotels. Don’t expect the normal luxury trappings of high-end accommodations; these are memorable for the uniqueness of the architecture rather than their spas and amenities. We especially like the Sextantio, which is a lovely space and a study in spartan luxury. To see how former inhabitants lived, stop by the Casa Grotta di Vico Solitario, a cave dwelling which has been renovated and furnished with artifacts of one family who lived here until they were relocated.

Both fascinating and poignant, this small museum is an excellent way to put Matera and its people into a historical and cultural context. Another modern trapping of Matera’s historic poverty is its rustic “cucina povera” cuisine. You can sample this simple yet delicious gastronomic tradition in one of the local cave restaurants, with dishes featuring legumes (mainly chickpeas) and pasta. Try crapiata, a filling bean and whole grain soup, and the local pasta made with grano arso, or toasted wheat kernels. Matera’s caves aren’t only in the old town; head to the surrounding hillsides and nearby Murgia Materana Park to explore the more than 150 “rupestrian churches”, frescoed caves used by locals for worship and retreat over the centuries and, in many cases, only recently rediscovered. We especially enjoyed visiting the Cripta del Peccato Originale, a small chapel in an isolated cave, considered the “Sistine Chapel” of cave churches for its rich internal frescoes and rediscovered in 1963.